Major cities across Canada and the US are facing 3 significant challenges: a massive housing shortage, excessive greenhouse gas emissions from new developments, and an oversupply of office spaces.

Toronto, for instance, closed out 2023 with a surplus of 2.7 million square feet of office space, according to the commercial real estate and investment firm CBRE. Meanwhile, our housing crisis remains in full force; the hybrid-and-remote-work model seems to be here to stay, at least for a while; and fluctuating market conditions and elevated interest rates are hanging the fate of office spaces in the balance. Therefore, it’s very tempting to conclude that the office is becoming obsolete, and repurposing these prime city locations into much-needed housing seems like a logical step forward.

Converting offices into residences seems like a great solution at first glance. Cities like Calgary are leading the way, introducing policies and funding to speed up conversion projects—an approach that has already started to show promising results, reducing their office vacancy rates and making way for thousands of new housing units. Through its “Downtown Office Conversion Programs”, the City of Calgary is co-investing in the conversion of vacant office buildings to housing, post-secondary academic spaces, student housing, hotels, and other uses that could revitalize their downtown. Their target is to remove 6 million square feet of vacant office space by 2031, with 17 conversion projects in the pipeline set to deliver over 2,300 new homes.

However, despite the exciting potentials, there are significant considerations that complicate office conversions.

Firstly, finding suitable office buildings for conversion to residentials is very challenging. Depending on the age and condition of the building, it may be more cost-effective to demolish and rebuild.

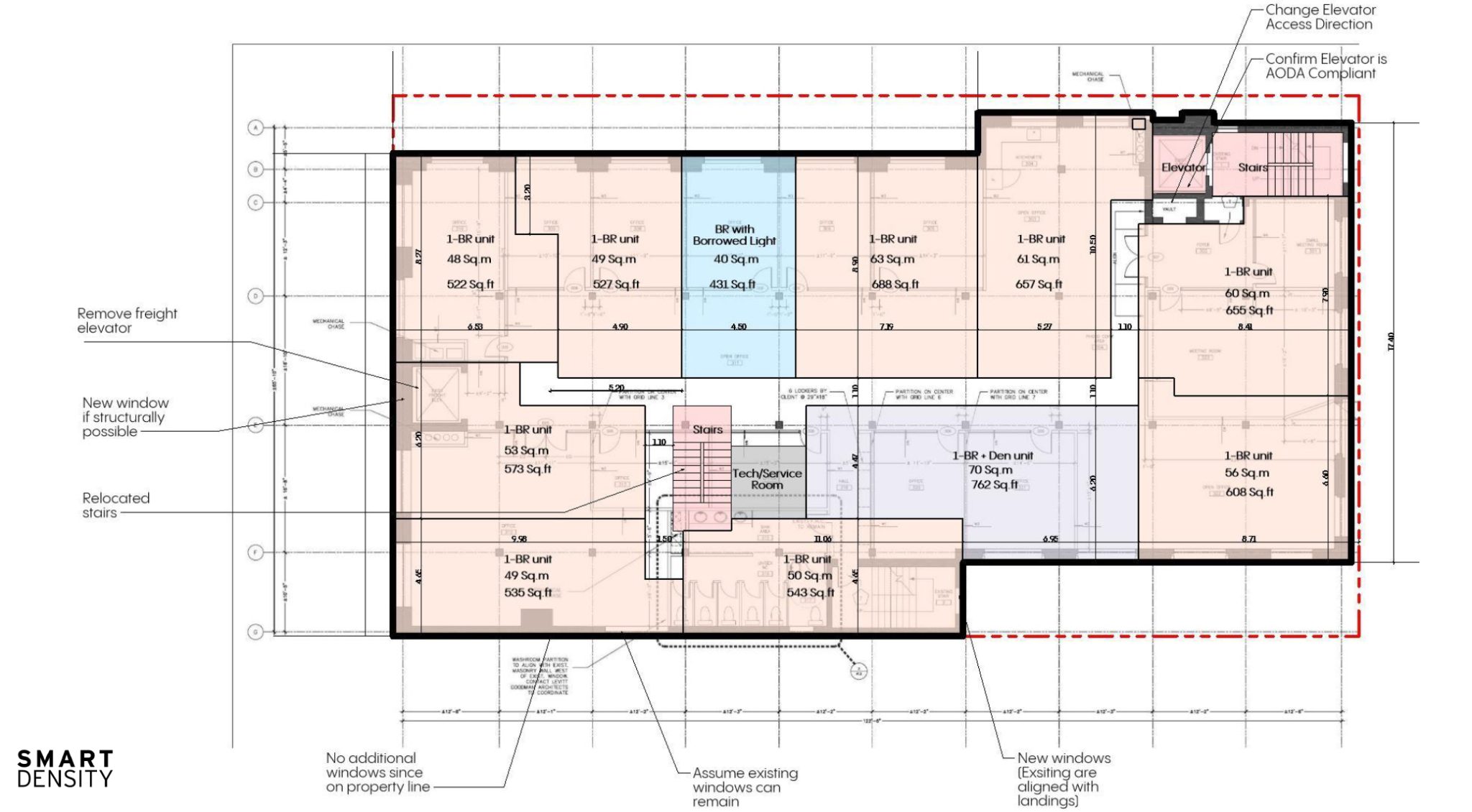

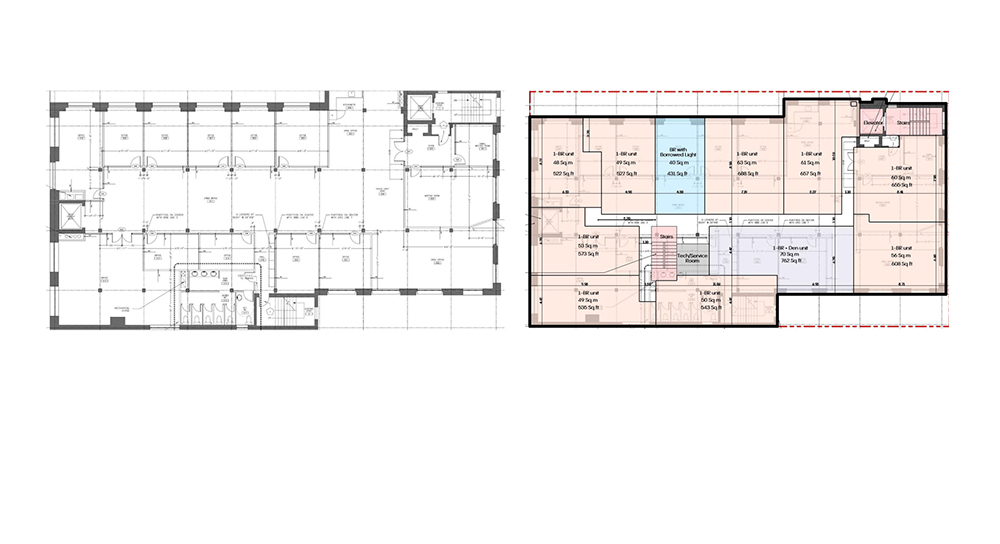

Older office buildings, especially pre-war ones, may be easier to convert because they were designed with ventilation standards that required windows in every office space, similar to residential layouts. Conversion of newer office buildings, on the other hand, could be more difficult and expensive to do. It could involve relocating windows, reconfiguring plumbing, changing electrical and HVAC systems, relocating stairs, altering elevator access, removing freight elevators, and more.

Office Conversion to Affordable Housing? A Case Study

Smart Density was approached by Kehilla, a non-profit affordable housing organization, to explore the feasibility of converting an existing, 5-storey office building in downtown Toronto to affordable housing.

This exercise strongly demonstrated the complexity of office to residential conversion.

Similar to most residential projects, the facade’s linear frontage is the main determining factor of the viability of the units, followed by the depth of the building.

In August 2023, a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) proposed specific criteria for identifying commercial office properties suitable for conversion to residential units. The final study concluded that only 9% of office buildings in the United States meet these criteria. While we currently don’t have a similar study on Canadian offices, it’s likely that the findings would align closely.

Furthermore, before we declare offices as outdated, we need to look deeper and ask why the trend of office vacancies isn’t affecting all properties equally. As Molly Westbrook, managing director of CBRE’s downtown Toronto office, emphasizes in this Toronto Star article: “Top-quality buildings that are newer and in more desirable locations are more attractive than older ones on the market. It really is about having that good, amenitized quality space right now.”

Is Office Really Dead?

What if the preference for remote work isn’t only because people generally dislike working in the office? What if our current offices fail to provide an attractive alternative workplace that would encourage people to choose a beautiful, healthy, and vibrant environment over the convenience of their isolated home? What if an underlying issue lies in our unreliable public transit system and the way we’ve designed our cities, which force people into long commutes and make it impossible for many to commute safely without using their cars and wasting hours in traffic jams?

But above all, we should remember that throughout history, cities have undergone numerous renewal periods. Cities are living systems, constantly changing, influenced by countless parameters and complex dynamics. What worked yesterday might not work today, but we might need it again tomorrow. We don’t even need to go far back in history to see this.

Look at Toronto’s 2.7 million square feet office space oversupply at the end of last year; a record-breaking oversupply largely due to the new office space released to the market. Why was 1.1 million square feet of new office space constructed in 2023, despite the record-high vacancy rates? It was a response to significant demand from U.S.-based tech companies during the pandemic, according to Marc Meehan, managing director of research for CBRE Canada. He notes, “During the pandemic, we saw a really significant influx of those companies that would otherwise have been traditionally located in the U.S., coming to Canada for affordable labour.” Shortly after, the demand from tech companies began to decline, but new constructions were already underway and they were delivered in 2023.

We are living in uncertain economic conditions, which puts the resilience of our cities and communities under great pressure. Demand for different sectors of our real estate market can change much faster than we can possibly respond to. What if instead of trying to react to unpredictable changes and trends, we become proactive and design our buildings and cities for flexibility from the start? So that our buildings could accommodate more than one use, swiftly adapt to our changing circumstances, and help us become more resilient and prepared for whatever the future holds.