How Angular Planes Perpetuate Toronto’s Housing Crisis

You don’t need to be an architect, urban planner, developer, or realtor to know that Toronto needs more housing. Ask anyone who is trying to find a new home to rent or purchase in the city. It’s competitive, expensive, and the options can be disappointing. Even as real estate prices are cooling, housing accommodations in Toronto are hard to secure.

Angular plane policies also aim to create a consistent look and feel from the street level so that transitions from low- to mid- to high-rise buildings are similar. While angular planes have helped advance Toronto’s skyline to become an interesting built form with diverse styles that work well together, they have also become a barrier to the goal of building more housing.

Watch our mini-webinar, The Cost of Angular Planes, to learn more about this planning tool and its effects.

How are Angular Planes Applied?

Angular plane policies are applied differently to mid-rise and tall buildings, and are described in the City’s mid-rise and tall building design guidelines. This is one of those urban planning tools that can be hard to grasp, and even harder to understand by simply reading lengthy policy documents.

Don’t worry, we can help! Check out our shop for straightforward summaries of these design guidelines, and take our mini-course, Planning for Non-Planners, which explains angular planes and other concepts in easy-to-understand videos.

Application for mid-rise buildings:

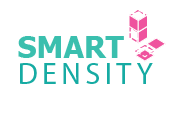

The maximum height at the front of a mid-rise building is equal to 80% of the street’s right of way. The right of way is the distance between the property lines on both sides of the street.

For example, if the right of way is 20 metres, the guidelines suggest that the building’s height facing the street should not be taller than 16 metres (which is 80% of 20). At 16 metres, the setback begins with a 45-degree angular plane applied from the edge of property line across the street.

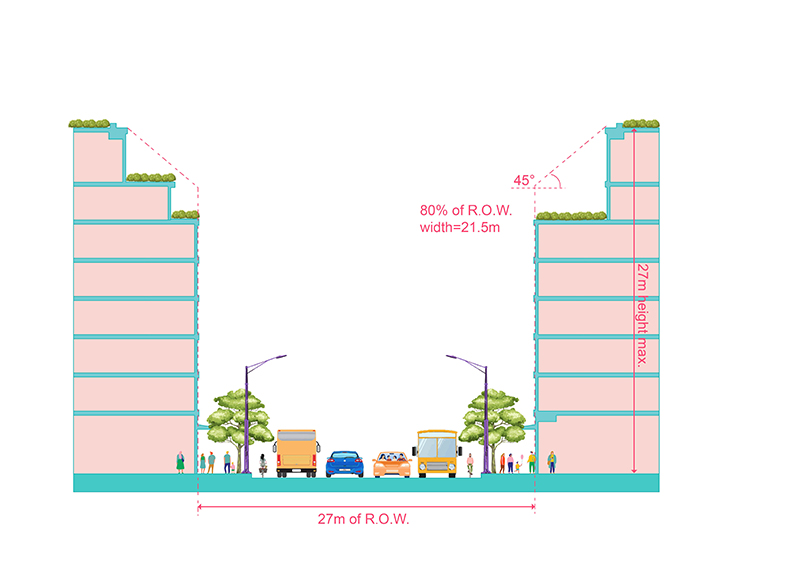

The mechanics change slightly at the building’s rear. The angular plane begins 7.5 metres in from the back property line or from the edge of the adjacent laneway (if there is one). Then, the building climbs between 7.5 and 10.5 metres in height before the setback begins, depending on whether the lot is considered shallow.

Application for tall buildings:

Nearby properties inform the application of angular planes for tall-buildings. For example, when a development is adjacent to areas that are designated “neighbourhoods” in the City’s Official Plan Land Use Map, the angular plane will be drawn on a 45-degree angle from the property lines of these more sensitive areas.

How do Angular Planes Impact Housing Supply?

The impact of angular planes extends beyond protecting the public realm from shadows and creating an appealing skyline. They prioritize low-density neighbourhoods, backyards, and the status quo at the expense of opportunities for new homes and new people in our city. Here’s how.

Picture the wedding cake building. When each tier is set back, it results in lost square footage. This space could have otherwise been homes for families. Even in the mildest of cases, where 11 or 12 units are lost due to the setback requirements, that equates to the same number of single-family homes that might be found in a short block.

When new mid-rise and tall buildings are proposed adjacent to single-family neighbourhoods, there is often vocal opposition from homeowners. These residents state that shadows will prevent them from enjoying their backyards and that new buildings will impede their space.

The question is: why are the concerns of wealthy homeowners prioritized over the intense need for more housing in the city?

Angular plane policies send a clear message: the backyards of Torontonians who can afford to live in single-family homes in the heart of city are more important than the numerous people who cannot access quality housing due to limited supply. Angular planes effectively protect the wealthy at the expense of everyone else, and they make responding to the current housing crisis more difficult than it should be.

From an architectural perspective, angular planes make design and development more complicated. They require specialized layouts for each new tier rather than a uniform design that can be applied to all levels. Placing vertical ducts and mechanical stacking is complex. These barriers add time and cost, resulting in less units for greater expense.

Should We Say Goodbye to Angular Plane Policies?

As a city and as a society, what are our values? Do we aim to maintain the status quo to benefit a minority of Torontonians? Or do we aim to create a more equitable city where people can access quality urban housing and lifestyles?

Protecting low-densities in the urban core is bad policy. We should be striving for greater density that supports walkable lifestyles, vibrant neighbourhoods, transit-use, and housing equity. Angular planes prevent us from achieving this goal.

If we don’t shift our thinking and approach, we risk further car dependency and suburban sprawl as more people will be forced to the city’s outskirts due to insufficient housing options in the core.

We need to ask ourselves whether preventing new homes from being built for the benefit of a handful of vocal homeowners is how we want to operate moving forward. If you ask me, angular planes do more harm than good, and they prioritize the wrong segment of our population. It’s time for these policies to evolve, to welcome new neighbours to our communities, and to build the Toronto of tomorrow.